FEW genera are more curious and intricate in their structure, than that to which our present article belongs. The plants which constitute the family of Asclepias are so peculiar in their habit, that they are easily recognized even by the inexperienced botanist, while their minute structure is so complicated, as to require not a little attention for its perfect development. This fine race of plants are so abundant in the United States, that every month of the summer season presents us a number of beautiful species. By far the most rich and gaudy of these in appearance is the Asclepias tuberosa, known by the vulgar names of Butterfly weed and Pleurisy root, and found in dry, sandy soils, pine woods, &c. from Massachusetts to Georgia. It is the Asclepias decumbens of Walter.

FEW genera are more curious and intricate in their structure, than that to which our present article belongs. The plants which constitute the family of Asclepias are so peculiar in their habit, that they are easily recognized even by the inexperienced botanist, while their minute structure is so complicated, as to require not a little attention for its perfect development. This fine race of plants are so abundant in the United States, that every month of the summer season presents us a number of beautiful species. By far the most rich and gaudy of these in appearance is the Asclepias tuberosa, known by the vulgar names of Butterfly weed and Pleurisy root, and found in dry, sandy soils, pine woods, &c. from Massachusetts to Georgia. It is the Asclepias decumbens of Walter.

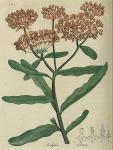

This genus has a five parted calyx; a five parted reflexed corolla; a nectary of five erect, cucullate leaves, each producing an inflected horn from its cavity; stamens united, with ten pollen masses hanging by pairs in their cavities. The species tuberosa is hairy, its leaves alternate, oblong-lanceolate; its branches cymose.

Class Pentandria, order Digynia. Natural orders Contortae, L. Apocineae, Juss.

The root of tins plant is large, fleshy, branching, and often somewhat fusiform. It is only by comparison with the other species that it can be called tuberous. The stems are numerous, growing in bunches from the root. They are erect, ascending or procumbent, round, hairy, green or red. Leaves scattered, the lower ones pedunculated, the upper ones sessile. They are narrow, oblong, hairy, obtuse at base, waved on the edge, and in the old plants sometimes revolute. The stem usually divides at top into from two to four branches, which give off crowded umbels from their upper side. The involucrum consists of numerous, short, subulate leafets. Flowers numerous, erect, of a beautifully bright orange colour. Calyx much smaller than the corolla, five parted, the segments subulate, reflexed and concealed by the corolla. Corolla five parted, reflexed, the segments oblong. The nectary or stamineal crown is formed of five erect, cucullate leaves or cups, with an oblique mouth, having a small, incurved, acute horn proceeding from the base of the cavity of each and meeting at the centre of the flower. The mass of stamens is a tough, horny, somewhat pyramidal substance, separable into five anthers. Each of these is bordered by membranous, reflected edges contiguous to those of the next, and terminated by a membranous, reflected summit. Internally they have two cells. The pollen forms ten distinct, yellowish, transparent bodies, of a flat and spatulate form, ending in curved filaments, which unite them by pairs to a minute dark tubercle at top. Each pair is suspended in the cells of two adjoining anthers, so that if a needle be inserted between the membranous edges of two anthers and forced out at top, it carries with it a pair of the pollen masses. Pistils two, completely concealed within the mass of anthers. Germs ovate, with erect styles. The fruit, as in other species, is an erect lanceolate follicle on a sigmoid peduncle. In this it is green, with a reddish tinge and downy. Seeds ovate, flat, margined, connected to the receptacle by long silken hairs. Receptacle longitudinal, loose, chaffy.

The down or silk of the seeds, in this and other species, furnishes an admirable mechanism for their dissemination. When the seeds are liberated by the bursting of the follicle which contains them, the silken fibres immediately expand so as to form a sort of globe of branching and highly attenuated rays, with the seed suspended at its centre. In this state they are elevated by the wind to an indefinite height, and carried forward with a voyage like that of a balloon, until some obstacle intercepts their flight, or rain precipitates them to the ground.

The down of different species of Asclepias is susceptible of application to various useful and ornamental purposes. If the fibre were sufficiently long to admit of its being woven or spun, it would approach more closely to silk in its gloss and texture, than any vegetable product we possess. As it is, it has been substituted for fur, in the manufacture of hats, and for feathers in beds and cushions. When attached by its ends to any woven fabric, this down forms a beautiful imitation of the finest and softest fur skins, and is applicable to various purposes of dress. The Asclepias Syriaca, from its frequency and the large size of its pods, has been most frequently employed for the foregoing purposes.

[Note A. A memoir on the cultivation and use of Asclepias Syriaca, by J. A. Moller, may be found in Tilloch's Philosophical Magazine, Vol. viii. p. 149. Its chief uses were for beds, cloth, hats and paper. It was found that from eight to nine pounds of the silk occupied a space of from five to six cubic feet, and were sufficient for a bed, coverlet and two pillows.

The shortness of the fibre prevented it from being spun and woven alone. It however was mixed with flax, wool, &c. in certain stuffs to advantage. Hats made with it were very light and soft. The stalks afforded paper in every respect resembling that obtained from rags. The plant is easily propagated by seeds or slips. A plantation containing thirty thousand plants yielded from six hundred to eight hundred pounds of silk.]

The root of the Butterfly weed when dry is brittle and easily reduced to powder. Its taste is moderately bitter, but not otherwise unpleasant. Its most abundant soluble portions are a bitter extractive matter and faecula. No evidence of astringency is afforded on adding solutions of isinglass or copperas, and hardly any traces of resin on adding water to alcohol digested on the root. The decoction afforded a flaky precipitate to alcohol, when the infusion did not. Boiling water may be considered the proper menstruum for this plant.

This fine vegetable is eminently intitled to the attention of physicians as an expectorant and diaphoretic. It produces effects of this kind with great gentleness, and without the heating tendency which accompanies many vegetable sudorifics. It has been long employed by practitioners in the Southern States in pulmonary complaints, particularly in catarrh, pneumonia and pleurisy, and has acquired much confidence for the relief of these maladies. It appears to be an expectorant peculiarly suited to the advanced stages of pulmonary inflammation, after depletion has been carried to the requisite extent. Dr. Parker of Virginia, as cited by Dr. Thacher, having been in the habit of employing this root for twenty five years, considers it as possessing a peculiar and almost specific quality of acting upon the organs of respiration, promoting suppressed expectoration, and relieving the breathing of pleuritic patients in the most advanced stage of the disease.

Dr. Chapman, Professor of medicine in Philadelphia, informs us that his experience with this medicine is sufficient to enable him to speak with confidence of its powers. As a diaphoretic he thinks it is distinguished by great certainty and permanency of operation, and has this estimable property, that it produces its effects without increasing much the force of the circulation, raising the temperature of the surface, or creating inquietude and restlessness. On these accounts it is well suited to excite perspiration in the forming states of most of the inflammatory diseases of winter, and is not less useful in the same cases at a more advanced period, after the reduction of action by bleeding, &c. The common notion of its having a peculiar efficacy in pleurisy, he is inclined to think is not without foundation. Certain it is, says he, that it very much relieves the oppression of the chest in recent catarrh, and is unquestionably an expectorant in the protracted pneumonies.

As far as my own observation with this plant extends, I am persuaded of its usefulness in various complaints. It appears to exert a mild tonic effect, as well as a stimulant power on the excretories. Like other vegetable bitters, if given in large quantities, especially in infusion and decoction, it operates on the alimentary canal, though its efficacy in this respect is not sufficient to entitle it to rank among active cathartics. I am satisfied of its utility as an expectorant medicine, and have seen no inconsiderable benefit arise from its use as a palliative in phthisis pulmonalis. Among other instances may be cited that of a young physician in this town, who died two years since of pulmonary consumption. He made great use of the decoction of this root, and persevered in it a long time from choice, finding that it facilitated expectoration and relieved the dyspnoea and pain in the chest, more than any other medicine.

The best mode of administering the Asclepias is in decoction or in substance. A teacup full of the strong decoction, or from twenty to thirty grains of the powder, may be given in pulmonary complaints several times in a day. In most cases after the inflammatory diathesis is in some degree subsided, it may be freely repeated as long as it agrees with the stomach and bowels.

Botanical References.

Asclepias tuberosa, Lin. Sp. pl.

Pursh, i. 183.

Michaux, i. 117.

Elliott, Car. i. 325.

Asclepias decumbens, a variety, Lin. Pursh, &c.

Apocynum Novae Anglise hirsutum radice tuberosa, floribus aurantiacis, Herman, Hort. 646. t. 647.

Dillenius, Elth. 35, t. 30, f. 34.

Medical References.

B. S. Barton, Collections, 48.

Thacher, Disp. 154.

Chapman, Therapeutics and Mat. Med. i. 346.

American Medical Botany, 1817-1821, was written by Jacob Bigelow, M. D.