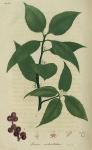

After the leaves have fallen in autumn, this shrub becomes conspicuous by its glossy scarlet berries, which adhere in bunches, for a long time, to the sides of the branches. Of the objects which impart any liveliness to this season of decay, the most noticeable are those which change the hue of their leaves from green to red, as the oaks, the vaccinia, &c. those which flower late, as the Hamamelis, and those whose fruit attains to maturity under the influence of frost, and appears fresh and vegetating, while other tilings are withering about them. The species of Prinos are of the last description.

After the leaves have fallen in autumn, this shrub becomes conspicuous by its glossy scarlet berries, which adhere in bunches, for a long time, to the sides of the branches. Of the objects which impart any liveliness to this season of decay, the most noticeable are those which change the hue of their leaves from green to red, as the oaks, the vaccinia, &c. those which flower late, as the Hamamelis, and those whose fruit attains to maturity under the influence of frost, and appears fresh and vegetating, while other tilings are withering about them. The species of Prinos are of the last description.

This genus consists of shrubs, a part of which are deciduous, and a part evergreen; bearing small lateral or axillary flowers. It is nearly related to the Ilices or Hollys, differing chiefly in the number of its parts. Its character is formed by a six cleft calyx, a monopetalous subrotate six cleft corolla, and a six seeded berry. The Prinos verticillatus has its leaves deciduous, oval, serrate, acuminate, slightly pubescent beneath; flowers axillary, aggregate.

These shrubs have usually been referred to Hexandria Monogynia. The present species and some others having different flowers on separate plants, Michaux was induced to place them in Dioecia. The natural orders to which they are assigned are Dumosae of Linn, and Rhamni of Juss.

The Black Alder, for so the shrub is usually called, is found in swamps and about the edges of streams and ponds from Canada to the Southern states. It is irregular in its growth, but most commonly forms bunches six or eight feet in height. The leaves are alternate or scattered, on short petioles, oval, acute at base, sharply serrate, acuminate, with some hairiness, particularly on the veins underneath. The flowers are small, white, growing in little tufts or imperfect umbels, which are nearly sessile in the axils of the leaves. Calyx small, six cleft, persistent. Corolla monopetalous, spreading, without a tube, the border divided into six obtuse segments. The stamens are erect, with oblong anthers. In the barren flowers they are equal in length to the corolla, in the fertile ones, shorter. The germ, in the fertile flowers, is large, green, roundish, with a short neck or style, terminating in an obtuse stigma. These are followed by irregular bunches of bright scarlet berries, which are roundish, supported by the persistent calyx, and crowned with the stigma, six celled, containing six long seeds, which are convex outwardly and sharp edged within. These berries are bitter and unpleasant to the taste, with a little sweetness and some acrimony.

The bark of the Black alder is moderately bitter, but inferior in this respect to many of our shrubs and trees. It discovers very little astringency either to the taste, or to chemical tests. A decoction which I made of the dried bark underwent no alteration on the addition of dissolved gelatin, and only changed to a dark green with the sulphate of iron. Alcohol produced hardly any change. The tincture, in alcohol, was found moderately bitter, and was not altered by water.

The Black alder has had a considerable reputation as a tonic medicine, perhaps more than it deserves. The late Professor Barton tells us, that the bark has long been a popular remedy in different parts of the United States, being used in intermittents and some other diseases as a substitute for the Peruvian bark; and on some occasions, he thinks it more useful than that article. " It is employed both in substance and in decoction, most commonly, however, in the latter shape. It is supposed to be especially useful in cases of great debility accompanied with fever; as a corroborant in anasarcous and other dropsies, and as a tonic in cases of incipient sphacelus or gangrene. In the last case," he says, "it is unquestionably a medicine of great efficacy. It is both given internally and employed externally as a wash."

Dr. Thacher recommends a decoction or infusion of the bark taken internally in doses of a teacupful, and employed also as a wash, for the cure of cutaneous eruptions, particularly of the herpetic kind.

I have had but little experience with the bark of the Prinos which gave me much satisfaction. Indeed the tests of tonic remedies are of a more ambiguous kind than those of most other medicines. Vegetable barks, which are bitter and astringent, are generally tonic, if they have no more striking operation; and in this property they differ in a degree somewhat proportionate to their bitterness and astringency. Judging by these criterions, the Prinos is not entitled to hold a very exalted rank in the list of tonics. As a bitter it is at best but of the second rate, and in astringency it falls below a multitude of the common forest trees.

The berries are recommended by the writers above cited, as possessing the same tonic properties with the bark. They certainly possess some activity, which, in large quantity, is not of the tonic kind. I have known sickness and vomiting produced in a person by eating a number of these berries found in the woods in autumn.

Botanical References.

Prinos verticillatus, Linn, Sp. pl.

Pursh, i. 220.

Prinos Grosnovii, Michaux, ii. 236.

Prinos padifolius, Willd. Enum Berol. 394.

Medical References.

B. S. Barton, Collections, ii. 5.

Thacher, Disp. 324.

American Medical Botany, 1817-1821, was written by Jacob Bigelow, M. D.