The Prickly Ash is a shrub of middling height, found in woods and moist or shady declivities in the Northern, Middle and Western states. It is rare in Massachusetts and the states north of it, its localities being very circumscribed. After I had taken pains to procure specimens from Connecticut, I accidentally discovered a thicket of the shrubs in a wood in Medford, six miles from Boston.

The Prickly Ash is a shrub of middling height, found in woods and moist or shady declivities in the Northern, Middle and Western states. It is rare in Massachusetts and the states north of it, its localities being very circumscribed. After I had taken pains to procure specimens from Connecticut, I accidentally discovered a thicket of the shrubs in a wood in Medford, six miles from Boston.

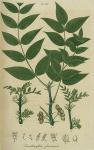

Late botanists have placed the genus Xanthoxylum in Pentandria Pentagynia, although it is dioecious, or rather polygamous. Its calyx is inferior, five parted; corolla none; capsules from three to five, one seeded. The X. fraxineum is prickly, the leaves pinnate; leafets ovate, subentire, sessile, equal at base; umbels axillary.

Linnaeus placed the Xanthoxyla in his natural order Dumosae, but Smith thinks them better arranged with the Hederaceae. Jussieu places them with his Terebintaceis affinia.

The branches of the Prickly ash are covered with strong, sharp prickles, arranged without order, though most frequently in pairs at the insertion of the young branches. Leaves pinnate, the common petiole sometimes unarmed and sometimes prickly on the back. Leafets about five with an odd one, nearly sessile, ovate, acute, with slight vesicular serratures, somewhat downy underneath. The flowers appear in April and May before the leaves are expanded. They grow in sessile umbels about the origin of the young branches, are small and greenish. I have observed them of three kinds, making the shrub strictly polygamous. In the staminiferous flower the calyx is five leaved, the leaves oblong, obtuse, erect. Stamens five with subulate filaments and sagittate four celled anthers. In the place of pistils are three or four roundish corpuscles supported on pedicels from a common base. The perfect flowers, growing on the same plant, have the calyx and stamens like the last; the germs are three or four, pedicelled, and having erect, converging styles nearly as long as the stamens. The pistilliferous flowers grow on a separate shrub. Calyx smaller and more compressed. Germs about five, pedicelled; styles converging into close contact at top, and a little twisted. Stigmas obtuse. All the flowers are destitute of corolla. Each fertile flower produces an umbel of as many stipitate capsules as there were germs in the flower. These capsules are oval, covered with excavated dots, varying from green to red, two valved, one seeded; the seed oval, blackish.

The bark of the Prickly ash has a slight aromatic flavour, combined with a strong pungency, which is rather slow in manifesting itself in the mouth. The leaves are more aromatic, very much resembling, in smell, the leaves of the Lemon tree. The rind of the capsule is highly fragrant, imparting to the fingers, when rubbed between them, an odour much like the oil of lemons. The odorous portion is an essential oil residing in transparent vesicular points on the surface of the capsules and about the margins of the leaves. The acrimony, which resides in the bark, has its foundation in a different principle; being separated by decoction, but not by distillation; at least none of it came over in my experiments, which were repeated with both the green and dried bark. The water in which the bark is boiled has a peculiar pungent heat, which is not perceived when the liquid is first taken into the mouth, but gradually developes itself by a burning sensation on the tongue and fauces. It retains this acrimony after standing a week and more. The leaves do not appear to possess the pungency of the bark, and impart no acrimony to the water in which they are boiled. They abound in mucilage, which coagulates in large films when alcohol is added to the decoction. They seem to possess more astringency than the bark, and strike a black colour with sulphate of iron, while solutions, made from the bark, are but moderately changed by the same test. The alcoholic tincture of the bark is bitter and very acrid. Its transparency is diminished by adding water, and after standing some time it becomes very turbid. "Whether the acrimony of this shrub resides in a peculiar acrid principle, or whether it belongs to the resin and becomes miscible with water in consequence of the presence of mucilage, may be considered as yet uncertain.

The Prickly ash has a good deal of reputation in the United States as a remedy in chronic rheumatism. In that disease its operation seems analogous to that of Mezereon and Guaiacum, which it nearly resembles in its sensible properties. It is not only a popular remedy in the country, but many physicians place great reliance on its powers in rheumatic complaints, so that apothecaries generally give it a place in their shops. It is most frequently given in decoction, an ounce being boiled in about a quart of water. Dr. George Hayward, of Boston, informs me, that he formerly took this decoction in his own case of chronic rheumatism with evident relief. It was prepared as above stated, and about a pint taken in the course of a day, diluted with water sufficient to render it palatable by lessening the pungency. It was warm and grateful to the stomach, produced no nausea nor effect upon the bowels, and excited little, if any, perspiration.

I have given the powdered bark in doses of ten and twenty grains in rheumatic affections with considerable benefit. A sense of heat was produced at the stomach by taking it, but no other obvious effect. In one case it effectually removed the complaint in a few days. I have known it, however, to fail entirely in obstinate cases, sharing the opprobrium of failure with a variety of other remedies.

The Prickly ash has been employed by physicians in some cases as a topical stimulant. It produces a powerful effect when applied to secreting surfaces and to ulcerated parts. In the West Indies much use has been made of the bark of another species, the Xanthoxylum Clava Herculis, in malignant ulcers, both internally administered and externally applied. Communications relating to its efficacy may be found in the eighth volume of the Medical and Physical Journal, and the fifth volume of the Transactions of the Medical Society of London.

By an ambiguity which frequently grows out of the use of common or English names of plants, the Aralia spinosa, a very different shrub, has been confounded with the Xanthoxylum. The Aralia, called Angelica tree, and sometimes Prickly ash, is exclusively a native of the warmer parts of the United States, being not found, to my knowledge, in the Atlantic states north of Virginia. Its flavour and pungency, as well as its general appearance, are different from those of the true Prickly ash. It is nevertheless a valuable stimulant and diaphoretic, and in Mr. Elliott's Southern Botany, we are told that it is an efficacious emetic. For the latter purpose it is given in large doses, in infusion.

The name Xanthoxylum, signifying yellow woody was originally given by Mr. Colden. The spelling has since been unaccountably changed to Zanthoxylon in a majority of the books which contain the name. The etymology, however, can leave no doubt of the true orthography.

Botanical References.

Xanthoxylum fraxineum, Smith, Nees' Cycl. No. 12.

Z. fraxineum, Pursh, i. 209.

Z. clava Herculis ß. Linnaeus, Sp. pl.

Z. ramiflorum, Michaux, Flora, ii. 235.

Fagara fraxini folio, Duhamel, Arb. v. t. 97.

Medical References.

B. S. Barton, Collections, i. 25,52; ii. 38.

Thacher, Dispensatory, sub Aralia spinosa.

American Medical Botany, 1817-1821, was written by Jacob Bigelow, M. D.